In a video titled “Why Is Term Insurance Better Than Whole Life Insurance?” uploaded to YouTube in 2016, financial guru Dave Ramsey confidently stated that, “… on average it’s making 1%-1.5% — horrible rate of return… it [whole life insurance] is one of the worst financial products on the market today.”

Such criticisms are common on the Internet.

Just about every financial guru, financial planner, and financial journalist agrees that no one should buy whole life insurance because it’s a terrible investment.

On Suze Orman’s blog, for example, Orman writes,

“Whenever someone tries to sell you a life insurance policy with some story that it is a fantastic way to invest, you are to shut down that conversation and never work with that person again.

Please listen to me: life insurance is an expensive way to invest. Anyone who is trying to sell you life insurance as an investment is not acting in your best interest.” (source: Is Life Insurance a Good Investment?, July 18, 2019)

Internet-famous financial blogger, “The White Coat Investor” AKA Jim Dahle, writes on his blog:

When you are shown an illustration, they always show you the projected amount, but you don’t ever get that.” (source: 8 Reasons to Avoid Whole Life Insurance, January 12, 2012)

Websites like The Simple Dollar publish articles telling consumers, “After running the numbers, Consumer Reports found that Treasury notes earning 2.17% would provide a higher return on your money”.

Are the experts and financial bloggers right? What about Consumer Reports?

In 2015, Consumer Reports published an article titled, “Is whole life insurance right for you?” In that article, Consumer Reports cites the guaranteed return on whole life insurance is 1.5%. They also state the expected future return is 3.5%.

Most whole life insurance policies sold today are dividend-paying whole life insurance policies. Insurers pay dividends because policyholders participate in the investment and operating experience of the insurer. Policyholders are, in effect, benefiting from the positive results of the business.

It should now be obvious to any casual reader why the overly simplistic claims made by critics can’t be true. The life insurance industry, like every other industry, is dynamic and changes and evolves over time. This is most apparent looking at historical dividend rates.

For example, in 1978, the dividend interest rate at MassMutual was 7.80%. By 1986, the dividend rate skyrocketed to 12.20% and the mortality and operating expenses did not have a net negative impact the overall dividend scale. As a result, policyholders received far more than the guaranteed rate, far more than 3.5%, and far more than originally illustrated by their insurance agent.

On the other hand, policyholders who bought whole life from MassMutual in 1990 and held to 2010, saw dividend rates (and the total dividend scale) drop during that time, from 10.50% to 6.70%. While mortality and operating expenses generally improved during this time, it was not enough to offset a falling dividend rate. Still, those policyholders made far more than the guaranteed rate in the policy and far more than 3.5% on their cash surrender values.

The Guardian Life Insurance Company of America is another example of a mutual insurance company paying variable dividends over time. It publishes its dividend rate history from 1959 to 2018 (as of this writing). Its dividend rate in 1959 was 3.30%. However, if Consumer Reports had used its then 3.30% projected future return assumptions for The Guardian, they would have been way off.

Guardian consistently increased the dividend rate during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s to peak at 13.25% in 1984 before slowing and gradually falling to 5.85% in 2018. So, for 30 years, policyholders consistently received more than they were promised (i.e. the guaranteed rate) and even more than the projected dividends.

MassMutual and The Guardian aren’t outliers, either. Reports from independent analysts, like the late Roger Blease (Blease Research’s “Full Disclosure”), show 20-year historical returns on whole life insurance exceed the 1.5% guaranteed return cited by Consumer Reports. And, in many cases, returns on whole life insurance exceed the “possible” 3.5% returns cited by Consumer Reports.

Indeed, one such report looked at policies issued in 1984 by 8 mutual life insurance companies. The policies were issued on males, rated non-smokers, aged 45 and males aged 55. Blease Research tracked the actual performance of those policies up to 2004 — 20 years. In every case but one, the participating whole life policies returned no less than 3%, and in most instances, policyholders received an annual compound return on cash values of between 4% and 5%.

Blease Research published numerous reports, each with different starting and ending points. The results always showed that the long-term returns on participating whole life insurance were always higher than the guaranteed illustrated rate, but ultimately depended on when the policy was purchased and how long a policyholder held onto it. The 20-year return on whole life, for example, is higher than the 10-year return.

Try Gemini Today! 123

The Gemini Exchange makes it simple to research crypto market, buy bitcoin and other cryptos plus earn Up to 8.05% APY!

And, for brave policyholders willing to stick it out for 30 or 40 years, the returns can rival more conventional investments.

MassMutual, for example, has one of the most comprehensive dividend performance studies in the life insurance industry. It shows the actual long-term return on various whole life products for both males and females of various ages.

That study shows that a policy purchased by a 45 year-old male 40 years ago has had an actual 40-year compound annual return of 4.80%. The policy was originally projected to return just 3.13%. A 35-year old female who purchased a whole life policy 40 years ago has earned a 40-year compound annual return of 5.86%. Her policy was projected to earn just 4.74%. And, a 50 year old male who purchased a policy 40 years ago has had a 40-year compound annual return of 5.89%. His policy was projected to return just 4.05%. MassMutual looked at a variety of different whole life insurance policies. Not all of these policies were designed specifically to build high cash values. However, all policies produced results that were much, much, better than originally illustrated to policyholders.

Other mutual life insurers can boast similar types of results.

But, some self-proclaimed financial experts and bloggers disagree. Todd Tresidder of “Financial Mentor,” is one such blogger who is highly critical of whole life insurance. His piece titled, “Whole Life Insurance – The Essential Guide” promises to educate readers about whole life insurance. In it, he states:

“The essence of life insurance is you give the company your money in the form of policy premiums and they give you back a package of benefits in exchange. The value of those benefits, on average, must be less than the value of the policy premiums you paid, after factoring in the time value and investment return on the money, in order for the insurance company to profit and pay salesmen commissions.

“If this weren’t true, then the actuaries designing these complicated investment contracts would get fired, and the insurance company would lose money and eventually go out of business.

“… It’s inviolable math.”

There are two basic ways we can look at Tresidder’s claim.

First, one could interpret Tresidder’s claim to mean that life insurers consistently make underwriting profits (i.e. that they ultimately pay out less in benefits than what they collect in premiums) and without those underwriting profits, the product (and thus the company) would go out of business. We can safely dismiss this idea as false since running underwriting profits is extremely rare in the life insurance business. The illustration Tresidder posts in his own guide shows that total benefits of the policy are never less than the total sum of all premiums paid, either in nominal or present value adjusted terms.

That this is the case is almost common sense. Underwriting profit in whole life insurance wouldn’t be very competitive and, in many ways, would actually be impossible due to the guaranteed growth factor of the cash surrender value.

However, insurers do make money by investing policy premiums in various ways before paying out claims or providing benefits to policyholders.

And, this is apparently what Tresidder thinks is wrong with whole life insurance as a product. What Tresidder argues is that the insurer must take premium dollars from policyholders and earn more with those premium dollars than it costs them to provide insurance, and cash values, to policyholders. For example, for every $1 in benefits paid to policyholders, the insurer must earn more than $1 in order to pay all its expenses — including the expense of providing benefits to its policyholders.

This is to be expected, but it’s also not unique to life insurance. This same phenomenon exists in every single business known to man, and to talk about “time value” and “investment return” on money invested without also talking about transaction cost is to talk of a fantasy world where there are only buyers and no sellers making profit.

In other words, his claim is that the insurer must earn more on policyholder premiums than what they pay back to policyholders in benefits and that this somehow means a policyholder can never come out ahead by owning whole life insurance. The implication is that a policyholder would be better off investing directly into something else, earning what the insurer is earning on those premiums, and cutting it (the insurance company) out of the process. But, in order to do that, the policyholder-turned-investor must essentially create a “costless profit”.

If only that were possible. It is, in Tresidder’s words, the “inviolable math” that makes it impossible.

Investment expenses are embedded in literally every single investment or asset an individual could buy in the open marketplace, from mutual funds, to individual stocks, to bonds, to precious metals, to real estate, to forex, to Bitcoin, options contracts, futures contracts, and event precious art and collectibles. It is an obvious (though often overlooked) fact that for every buyer in a marketplace, there is a seller. And for every seller, there is the profit motive. Sellers do not sell, on average, at a loss, else they cease to exist as sellers. And, if enough sellers leave the marketplace, there is no marketplace.

And, any investment with any amount of expense — which is to say every investment — suffers from the same so-called “problem” which is inherent in free trade.

That financial businesses do not sell financial products and services for free is obvious. Even in cases where expense ratios on mutual funds are very low, or appear to be nonexistent, there are embedded expenses created by — among other sources — lending those mutual fund shares to short sellers. That investments, always and everywhere, have these transaction and operating expenses is obvious. These expenses are deducted from the gross value of one’s investment, resulting in a lower value than the “costless value” of the principal amount invested (or, in Tresidder’s words, “the value of the policy premiums you paid, after factoring in the time value and investment return on the money”).

To reiterate, in order to pay a net return of 5% on cash values or death benefits in a whole life policy, the insurance company may have to earn 6% on premium dollars paid by policyholders, and in any case they must earn at least 5%.

OK, but so what? Banks must do the exact same thing to pay interest to savings account and CD holders. Mutual fund companies must to the exact same thing to offer mutual fund returns to mutual fund investors. Hedge funds (which Tresidder is very familiar with) must do the exact same thing to deliver returns to hedge fund investors. Stocks must earn a higher return, on average, than the broker fees required for trading. Real estate sellers, on average, must sell at a profit. Yes, there is “friction” in trading from the perspective of the buyer, and this is precisely what makes markets work.

It is only in an unreal fantasy world where costless investments exist.

Since there are no costless investments, what is the relevance of Tresidder’s statement? That whole life insurance has expenses? OK but, again, so what?

The saving grace of mutual life insurers, and by extension dividend-paying whole life insurance, is that the profits of a mutual life insurer belong to its whole life insurance policyholders, who are legal owners and members of the company. In other words, the owners are also the customers. Those profits paid to policyholders are paid out via an annual dividend, which helps defray the normal and natural expenses of the insurance.

The dividends, in turn, are typically used to buy additional paid-up life insurance, which builds its own cash value and generates its own dividends. Historically, those dividends have been significant, making the total return on whole life cash values very competitive against traditional non-guaranteed investments. And, that competitive return has helped policyholders avoid the risk of speculative investments without sacrificing much, if any, return on their money.

And, this really gets to the heart of the matter.

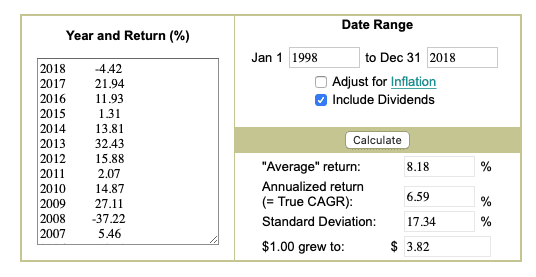

According to DALBAR, the average equity investor’s return over the last 20 years has been just 5.29%. The average return for fixed income investors over the last 20 years has been 0.44%. Even the raw, bare-bones, S&P500 index itself did just 6.59% over the last 20 years, with dividends reinvested:

The actual growth of the index during this period was only 4.62%.

Even if one could invest directly in the S&P500 index (which isn’t actually possible), and one assumes minimal investment fees and a low tax rate while doing so, the historical growth of the market index itself struggles to outpace the long-term average return of high cash value whole life insurance policies from the major mutual life insurers.

If one then adds in the cost of term life insurance, which draws investable dollars away from investments to pay for term life premiums, then an investor’s return on a “buy term, invest the difference” strategy — net of industry-average fees, taxes, and term life premiums — has historically failed to outperform a strong, high cash value, dividend-paying whole life policy.

But, the past is not the future, and that’s kind of the whole point.

Even the critics fully acknowledge that the future is unknowable.

Ramsey openly states on his website that, “If you wait too long to buy life insurance, you leave your family vulnerable if something unexpected happens to you… what happens if you buy a 10-year policy and have medical issues down the road that raise the cost of your next plan—or worse, make it so you can’t get coverage at all?”

Orman echoed this sentiment in 2003 on the Money Life show hosted by Chuck Jaffe, but she directed the obviousness of an unknowable future towards the subject of investing. At that time, Orman insisted the best investment for individuals was to pay down their home mortgage to the exclusion of investing because stocks were so unpredictable. When Jaffe and a CFP asked how she could be so sure that her advice was correct, Orman’s response was, “only time will tell if it’s good advice.”

Jim Dahle, in his 2012 blog post, “Don’t Rely On Predicting The Future”, tells readers: “It is an interesting exercise to go to the library (or better yet used book store) and get the older investing books. 5, 10, 15, even 20 years old. Some of the advice and conjecture about the future is utterly laughable… I am amazed at how often the conversation turns to predicting the future. People seem to think this is a requirement for investing success. It isn’t. What is essential is a plan that is highly likely to succeed no matter what happens in the future.”

And, in a December 2016 interview on The Wealth Standard, Todd Tresidder tells the host, “The essence of investing is you’re putting capital at risk into an unknowable future… it’s an unknowable future, we have to be clear on that… reward is ultimately the thing that everybody seeks, everybody is focused on, everyone salivates over… and it’s the one thing you can’t control because it’s determined by the unknowable future.”

Never were truer words ever spoken. And yet, that they are common sense is what makes the claims made by whole life insurance critics even more baffling. As much as we all want to possess the predictive powers of Cassandra of Troy, no one can actually predict the future value of non-guaranteed investments. With traditional investments, we can’t know the value of our savings when we die, and we can’t know the value of our savings when we need it in the future for retirement or something else.

Whole life insurance is, and always was, the solution for this problem. It works precisely because it is not an investment. It is not a speculation on future asset values. It is not predicated on taking risks or making predictions. It is predicated on transferring risks away from the policyholder. It creates certainty out of uncertainty. It solves the eternal problem of predicting one’s financial future without having to actually predict the future.

Even though we can’t know the future dividends of any of the mutual life insurance companies doing business today, we can know the guaranteed cash value of the policy. That aspect of whole life insurance is a known quantity. And, whether or not critics acknowledge it, that is the only known quantity in the financial world. No other product accomplishes what whole life insurance does. None.

The moment you can predict your own future, you don’t need life insurance. But, as critics freely acknowledge, that’s not the world we live in. The world we live in gives you two basic choices. You can either make your financial plans based on a known future outcome or… you can speculate on your future and hope for the best.

Which option will you choose?

Author Bio

David C Lewis, RFC is an independent life insurance agent, a Registered Financial Consultant, and the founder of Monegenix®. For more information about his unique approach to life insurance and financial planning, go to www.monegenix.com.